Understanding New Jersey’s Gradual Abolition Act

By: Tessa Payer, Museum Specialist at the Wayne Museum and Staff Member of the Passaic County Department of Cultural & Historic Affairs

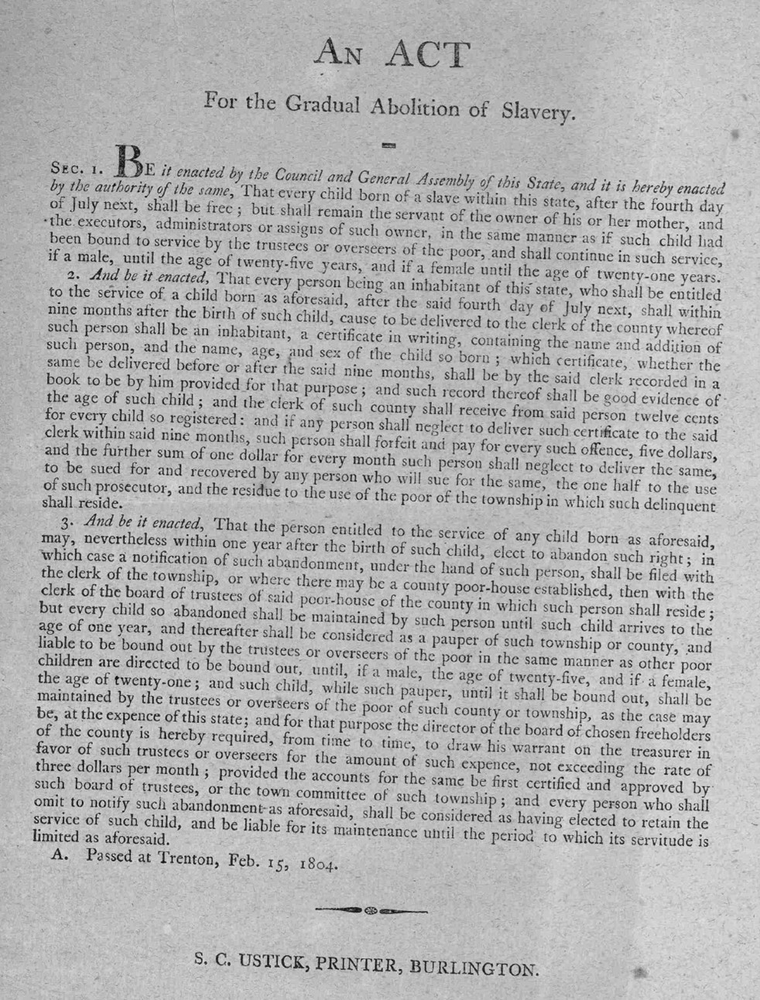

On February 15th, 1804- almost 175 years after enslaved African individuals were first brought to New Jersey, the state legislature passed “An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery.” New Jersey was the last Northern state to start the emancipation process, and even then, slavery would not legally end in the state until January 23rd 1866, when the Thirteenth Amendment was formally ratified.

In the decade before the Gradual Abolition Act was passed, there were about 11,400 African Americans enslaved in New Jersey. About 2,300 of these individuals lived and labored in Bergen County, which, according to author Christopher Matthews, would “consistently [have] the highest percentage of its population who were enslaved among all New Jersey counties.” Wayne Township was one of many towns included in this statistic, since it was considered part of Saddle River Township in Bergen County before its 1847 establishment.

What was the impact of the Gradual Abolition Act on those enslaved in Wayne Township? Though we don’t have a record of their personal thoughts or feelings, by reviewing the various parts of the 1804 Act, we’ll explore the experiences of the enslaved individuals who lived in the township.

Tom was born in New Jersey in 1811. His mother was an enslaved African American woman. According to surviving documentation, as well as the Act itself, he was “free born”. In reality, his legal status was in limbo. According to the first part of the Gradual Abolition Act, children born to enslaved mothers after July 4th, 1804 would be considered free. However, they were expected to keep working- unpaid- for their mother’s enslaver until they reached their majority, which varied based on gender. Tom would have to wait until he turned 25 to truly be free.

The Gradual Abolition Act did not provide an immediate end to enslavement in New Jersey- in fact, it opened the door to a new form of forced labor. Author James Gigantino refers to children, like Tom, who were born to enslaved mothers after 1804 as “slaves for a term.” The fact that their labor was limited to a specific period of time resembles an indenture or apprenticeship. However, while apprentices and indentured servants often received goods in return for their service and were protected by a legal contract, “slaves for a term” had no such benefits. They could only rely on the Gradual Abolition Act to define their legal status. Enslavers took advantage of its vague wording to treat these children as their property. Gigantino states that “sales of slaves for a term represented 17 percent of all bound Black laborers advertised for sale in New Jersey newspapers between 1804 and 1824.

In 1827, by the time he was sixteen, Tom was laboring for Jacob T. Field, who lived in Pompton Township in Bergen County; this may have been Reverend Jacob Ten Eyck Field, minister of the Pompton Reformed Church from 1816-1827. We don’t know if Tom’s mother was enslaved by Field, or if he had been sold and purchased before. In June 1827, however, Jacob T. Field sold “a certain free born negro boy named Tom” to Wm. W. Colfax “for and in consideration of the sum of one hundred dollars.” The accompanying bill of sale, which survives in the Wayne Museum’s collection, notes that Tom was “to serve the said Wm. W. Colfax until he arrives at the age at which the law of New Jersey frees them.” Tom would have to wait 9 years until his freedom was legally recognized.

The Wayne Museum has seven bills of sale reflecting the sale and purchase of African American children born after 1804; brothers John and William, who were sold along with their mother, Sarah; 15 year old Mary; 2 year old Sal, sold with his mother Deyoun; 10 year old Phebe; and, of course, 16 year old Tom. For these children, the Gradual Abolition Act did not truly end their enslavement, but created the status of “slaves for a term.” White and Black residents of New Jersey recognized the impact of the Act’s first paragraph. In 1841, “citizens of Paterson” issued a pamphlet pointing out these flaws, particularly the Act’s term of service. They stated:

“We cannot but regard compulsory servitude, coming in after a declaration of freedom, as a continuation of slavery for the time being: hence we look upon the servants for years…as slaves so long as they remain under age, slaves to all intents and purposes…We are desirous, gentlemen, that the servitude for years should be entirely abolished, or its duration limited to a shorter term, and its condition greatly modified.”

Annich was enslaved by members of the Van Riper family in Wayne from at least 1807 to the 1850s. Many of her personal details remain unknown; later census records suggest that she was born ca. 1782-1784, but we don’t know who were parents were, if she was born into enslavement on a Van Riper property, or if she was sold as a child. However, because of New Jersey’s registration system, we know that Annich had at least two children during her lifetime, both of whom were born after 1804.

The registration system was introduced as a way to enforce the Gradual Abolition Act- enslavers were technically required to register children born to women they enslaved within nine months after their birth. The name, age, and gender of a child were written down by county clerks in “Black Birth Books”. This allowed the years of service required before these children reached their majority to be tracked. With no means of enforcing the Act, however, many slaveowners skirted the registration or did so long after the deadline. After 1811, about 70% of all birth registrations in Bergen County were late. By registering children late, or altering their birthdates, enslavers tried to extend the service of “slaves for a term”.

Annich’s two children were amongst these late registrations. On November 26th, 1824, the county clerk recorded “Uriah R. Van Riper of the State of New Jersey, Bergen County, Saddle River Township, a farmer, has two Black children born at his house to offer on record.” Dine was born on October 12th, 1811, when Annich was in her late twenties, while Cuff was born on April 8th, 1818; meaning that Annich was likely in the early stages of her pregnancy when she was purchased by Uriah Van Riper from his father’s estate the previous year. We don’t know who Dine and Cuff’s father was, or who named them. Dine may be a reference to the Old Testament’s Dinah. Cuff appears to be a reference to Cuffee, a name emerging out of a tradition shared by several West African cultures in which children are named after the day of the week that they were born on.

The births of 989 African American children were recorded in Bergen County as part of the registration system. Today, Bergen County’s “Black Birth Books” serve as an opportunity to gain a human perspective on the Gradual Abolition Act and enslavement in the area. While the thoughts and feelings of Annich and her children have not been recorded, the fact that we have their names provides a human touch on the act. Its flaws- a lack of enforcement, the ability for enslavers to keep viewing “slaves for a term” as property- were not just legal decisions- they had a very personal impact on Cuff, Dine, and over 900 other children.

Gigantino refers to this section of the act as the “abandonment clause”. Slaveholders were required to support children born after 1804 until they were a year old- then, they could legally turn their care over to the overseers of the poor. These children would then be indentured out to other families; as mentioned before, though, they had no legal protections or compensation. County overseers of the poor were allowed to pull $3 a month from the state treasury for the care of these children.

This financial aspect of the “abandonment clause” came under particular criticism by White residents. While this money was supposed to be for the maintenance of African American children abandoned by their mothers’ owners, some enslavers saw it as a way to work the system in their favor; they could turn a child over to the overseers of the poor, then take their indenture, exploit their labor, and take the monthly payment for themselves. In this way, as Gigantino notes, the state “continued its role as a slave broker.” Others simply criticized financially supporting Black children. The “abandonment clause” was eventually repealed in 1811.

Bergen County enslavers led the way in protesting the act, particularly the “abandonment clause.” One group of slaveholders declared the Act “unconstitutional, impolitic, and unjustly severe”, while a petition from January 1806 (and signed by 714 men from Bergen County) patronizingly stated that “holders of such slaves [deserve] an equal right to the unlimited services of their issue or offspring and more especially as they protect, clothe, and support the parents.” Two generations of Van Ripers- Uriah, his brother Richard, and son Jacob- were amongst 54 men from Preakness who petitioned the State Legislature to repeal the Gradual Abolition Act, stating “that your petitioners, sensible of the inconvenience already arisen, since the passing of the Act for the abolition of Slavery, and dreading the intolerable burden of accumulating Taxes, which will infallibly take place under the continuation of said Act.” Imagine the reactions of en

slaved people like Annich, who labored for the Van Ripers for her entire life and may have overheard their conversations about the act.

The Gradual Abolition Act, as shown above, started the slow process towards ending enslavement in New Jersey. However, it was more than just a statewide law. It had a personal impact on enslaved and free African Americans living in the area that would become Wayne Township- Tom, Annich, Cuff, Dine, and more.

In February 2021, “Slavery at Dey Mansion Washington’s Headquarters and Its Passaic County Environs: A Research Report on Archival Sources, Material Culture and Interpretive Themes” was released by Hunter Research, Inc. It was prepared for the Passaic County Department of Cultural & Historic Affairs and the Friends of Passaic County Parks, with support from the New Jersey Council for the Humanities. This report traces the history of enslavement during various family residences at the Dey Mansion, as well as Passaic County and Northern New Jersey more broadly. It is a fantastic source on the experience of enslaved people in the region and can be accessed online- link forthcoming.

The Wayne Museum operates under a shared services agreement between the Township of Wayne and the County of Passaic. The County manages and operates the Wayne Museum on the Township’s behalf through the County’s Department of Cultural & Historic Affairs.

Bibliography

An act for the gradual abolition of slavery…Passed at Trenton Feb. 15, 1804. Burlington: S.C. Ustick, 1804. From the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/resource/rbpe.0990100b/?sp=1.

Gigantino, James J. The Ragged Road to Abolition: Slavery and Freedom in New Jersey, 1775-1865. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014.

Matthews, Christopher N. "The Black Freedom Struggle in Northern New Jersey, 1613-1860: A Review of the Literature." Montclair State University. Prepared for the Passaic County Department of Cultural & Historic Affairs. July 2019. https://www.montclair.edu/anthropology/research/slavery-in-nj/.

Alemy, Alexis; Boyce, Eryn; Craft, Rachel; Harshbarger, Patrick; Lee, James. "Slavery at Dey Mansion Washington's Headquarters and Its Passaic County Environs: A Research Report on Archival Sources, Material Culture and Interpretive Themes." Hunter Research Inc, March 2021.

Williams, Noelle Lorraine. “New Jersey, The Last Northern State to End Slavery,” NJ Historical Commission. Accessed December 29th, 2022. https://nj.gov/state/historical/his-2021-juneteenth.shtml.

“New Jersey Passes Law Delaying End of Slavery for Decades,” A History of Racial Injustice. Accessed December 29th, 2022. https://calendar.eji.org/racial-injustice/feb/15#:~:text=New%20Jersey%20passed%20a%20law,ending%20enslavement%20within%20its%20borders.

“History.” Pompton Reformed Church. Accessed January 11th, 2023. https://churches.rca.org/prc/History.html.

Jacob Field to William Colfax. Bill of Sale, Tom, June 22nd, 1827. From the Wayne Museum.

George Ryerson to William Colfax. Bill of Sale, Nelly and son, July 29th, 1816. From the Wayne Museum.

John Vreeland to William W. Colfax. Bill of Sale, Sarah, John and William, November 1st, 1823. From the Wayne Museum.

Simeon J. Van Ness to William W. Colfax. Bill of Sale, Mary, December 10th, 1826. From the Wayne Museum.

Charles Harrison to William W. Colfax. Bill of Sale, Deyoun and Sal, February 21st, 1831. From the Wayne Museum.

Henry Vreeland to William W. Colfax. Bill of Sale, Phebe, March 1st, 1832. From the Wayne Museum.

Citizens of Paterson. Address to the Legislature of New-Jersey in Behalf of the Colored Population of the State. (Paterson: Day & Warren, 1841). https://dspace.njstatelib.org/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10929/69016/J326a227.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Butler, Nic. “Recall Their Names: The Personal Identity of Enslaved South Carolinians,” Charleston County Public Library. October 2nd, 2020. Accessed January 5th, 2023. https://www.ccpl.org/charleston-time-machine/recall-their-names-personal-identity-enslaved-south-carolinians.

“Naming Culture in the Book of Negroes,” Atlantic Loyalist Connections. February 21st, 2018. Accessed January 5th, 2023. https://loyalist.lib.unb.ca/atlantic-loyalist-connections/naming-culture-book-negroes.

Black Births, 1804-1846. New Jersey County Court (Bergen County). FamilySearch.org. Page 134. New Jersey, County Marriages, 1682-1956. A microfilm of the original records, which are stored in the Bergen County Administration Building in Hackensack, NJ, was accessed at https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939Z-1ZSD-QM?cc=1803976&wc=9XRM-VZ3%3A146364601.

Labaw, George Warne. Preakness and the Preakness Reformed Church. New York: Board of Publication of the Reformed Church in America, 1902.