Mapping Rural Wayne and the 1870s Atlas of Passaic County

By: Tessa Payer, Museum Specialist at the Wayne Museum and Staff Member of the Passaic County Department of Cultural & Historic Affairs

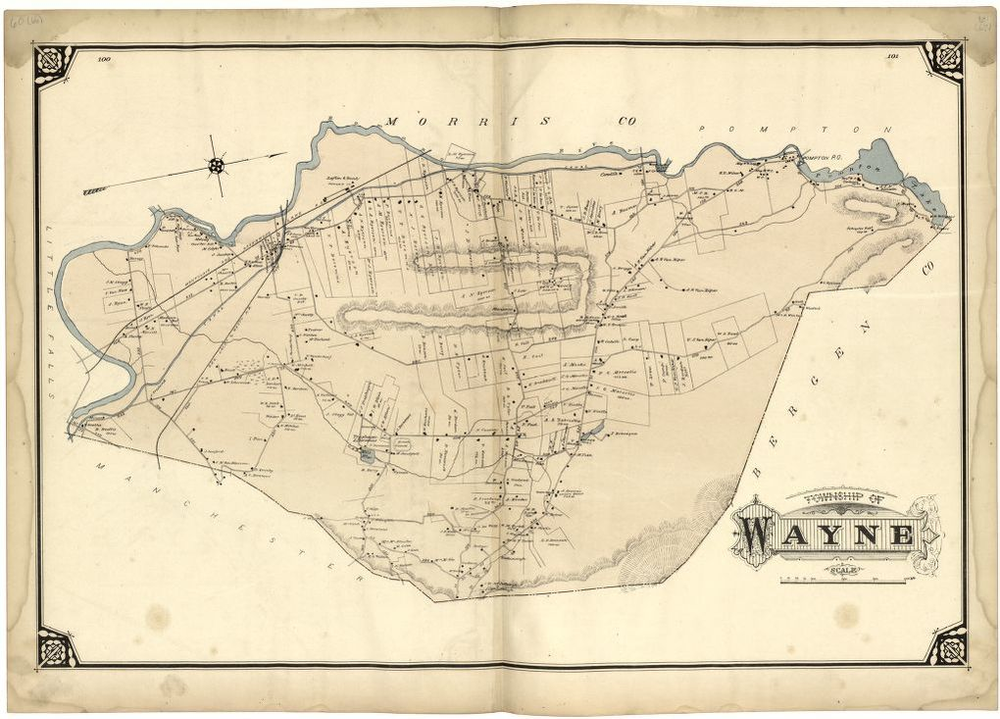

In the 1870s, E.B. Hyde & Co published an Atlas of Passaic County, New Jersey, promising topographical, geological, and historical information, as well as illustrations, relating to the county. Among the atlas’s 50 pages is a map of the township of Wayne, displaying property designations, roads, railroads, and more. Though the boundaries of Wayne haven’t changed dramatically, 20th century suburban development has greatly altered the township’s landscape. Studying the Atlas’s map of Wayne is like opening a time-capsule to the rural Wayne of the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries.

While the township, as depicted in this map, doesn’t show the housing developments, shopping centers, and malls that cover Wayne today, that hardly means that 1870s Wayne was a quiet place. The Atlas shows numerous property designations, labelled with the name of the property owner. These larger tracts of land show the numerous farms that made up Wayne Township. These properties were rooted in family ties; often, they were passed down through generations, transferred hands with marriages, or were divvied up after a death. These properties made up the bustling agricultural economy of the township. According to the 1860 agricultural returns for New Jersey, Wayne produced 2,009 bushels of wheat, 8,205 bushels of rye, 22,987 bushels of corn, 12,933 bushels of oats, 486 pounds of wool, 23,012 bushels of potatoes, 4,412 bushels of buckwheat, and 3,135 tons of hay. The township’s 615 milk cows produced 75,0004 pounds of butter. Though the properties seem relatively sparse in the map, in reality they would’ve been dotted with outbuildings. Stables and pastures would have housed livestock, including Wayne’s 364 sheep, 274 horses, 8 donkeys and mules, 211 working oxen, 602 cattle, and 530 swine. Later residents of Wayne attest to the agricultural landscape. Bertha Hopper remembered sitting on the porch of the Van Riper-Hopper House, gazing out at “pastures all around, where cows and horses grazed,” while Mrs. Dawes recalled that on her family’s farm, “there were 300 or 400 acres; we kept horses, cows, pigs, chickens and all such. I recall great fields of wheat as the wind blew- it was so beautiful as it waved like that of the sea.”

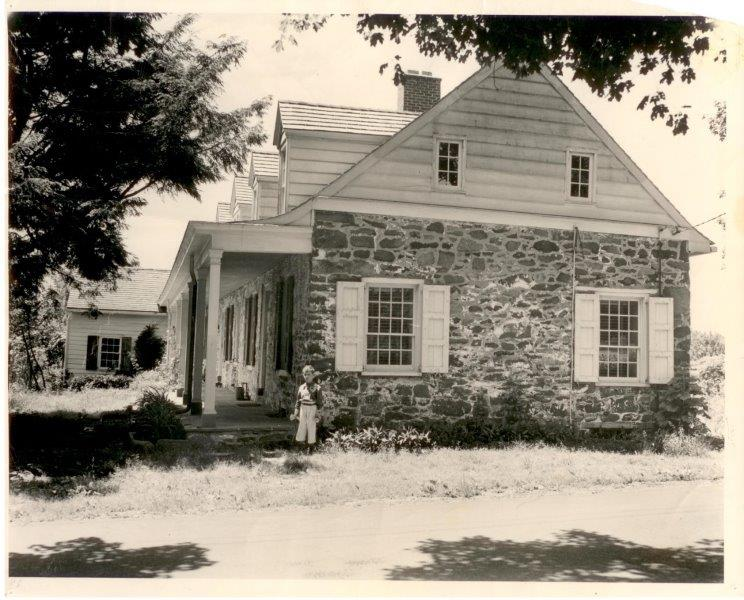

The Van Riper family of the Van Riper-Hopper House serve as one example of a well-to-do farming family in Wayne. As per the Atlas, the property that includes today’s Van Riper-Hopper House was owned by U.J. Van Riper and totaled at 180 acres; one of the largest properties in the township. As per the 1870 US census, Uriah Van Riper was the head of his household, a 57-year-old farmer with personal property valued at $400 and real estate valued at $10,000. The Van Riper property was occupied by his family- wife Anna and two daughters, Mary Ann

and Sarah Elizabeth- as well as four African American individuals- Harry Merselis (70 years old), Sarah Ogden (31), Susan Ogden (9), and William DeMott (5). Sarah, who previously appeared in the 1860 census as a servant working for the Van Ripers, was likely a live-in domestic servant, accompanied by daughter Susan. Harry Merselis is identified as a farm laborer. Though his wage is unknown, William Berce writes in Under the Sign of the Eagle that average wage for a farmhand, including room and board, was about $12 per month. Though their names don’t appear on the Atlas, African American farm workers were a key part of Wayne’s agricultural experience; many previously labored as enslaved individuals, and by the time of the Atlas, served as paid farm laborers.

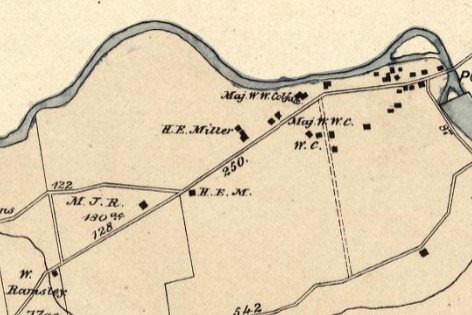

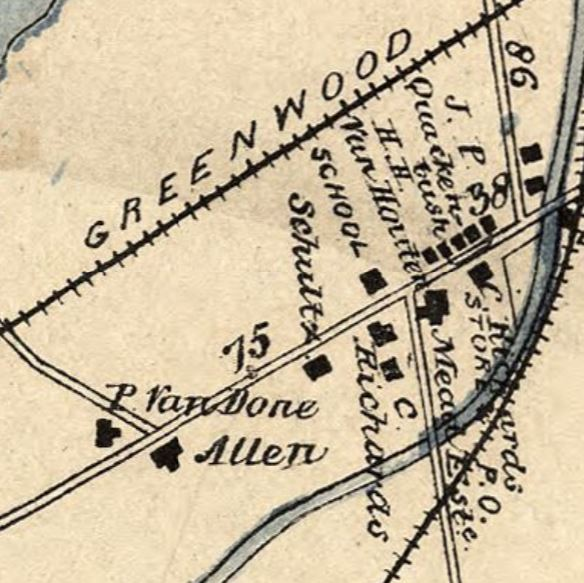

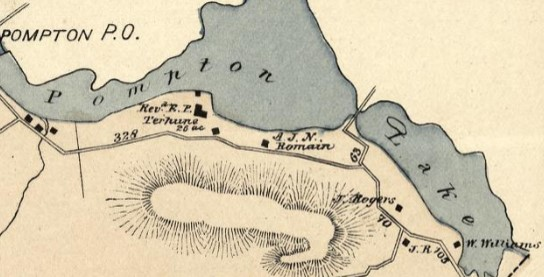

Figure 3-9- Four family homes in Wayne, along with their locations on the 1870s Atlas: the Van Riper-Hopper House (photographed in the 1930s), the Dawes House (built in the early 1800s for George Washington Colfax, who was raised in the Schuyler-Colfax House), the Mead-Van Duyne House (photographed on its original site before its 1970s move to Berdan Ave), and Sunnybank (home of the Terhune family). All photos from the Wayne Museum. Atlas clippings from from the “Atlas of Passaic County, New Jersey.” From the Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3813pm.gla00164/?sp=45.

Since we’ve focused on the Van Riper family, it only seems fair to point out the Wayne Museum’s other sites on the Atlas.

North of Uriah J. Van Riper’s property, along Hamburg Turnpike, we can find a series of buildings belonging to “Maj. W.W. Colfax”. While the Schuyler-Colfax House is all that remains of the extended Colfax family estates today, that section of Hamburg Turnpike was once home to countless buildings; the Dawes House, originally built for one of William and Hester Colfax’s children, the toll house, where travelers on Hamburg Turnpike paid their way, as well as farm outbuildings, former enslaved quarters, and more.

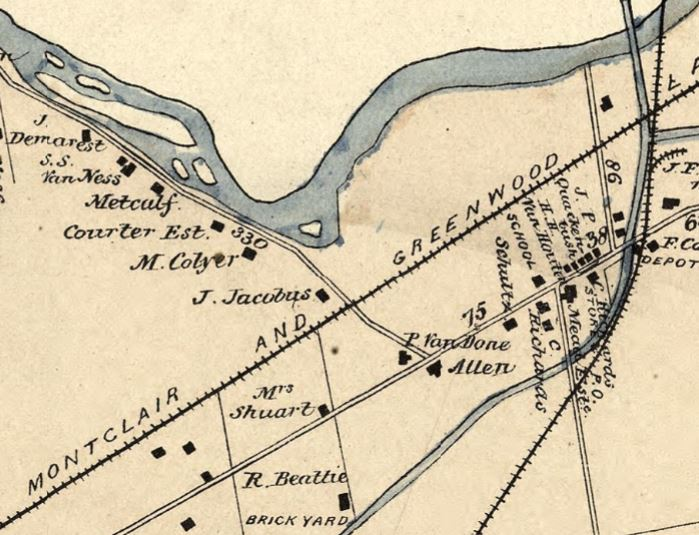

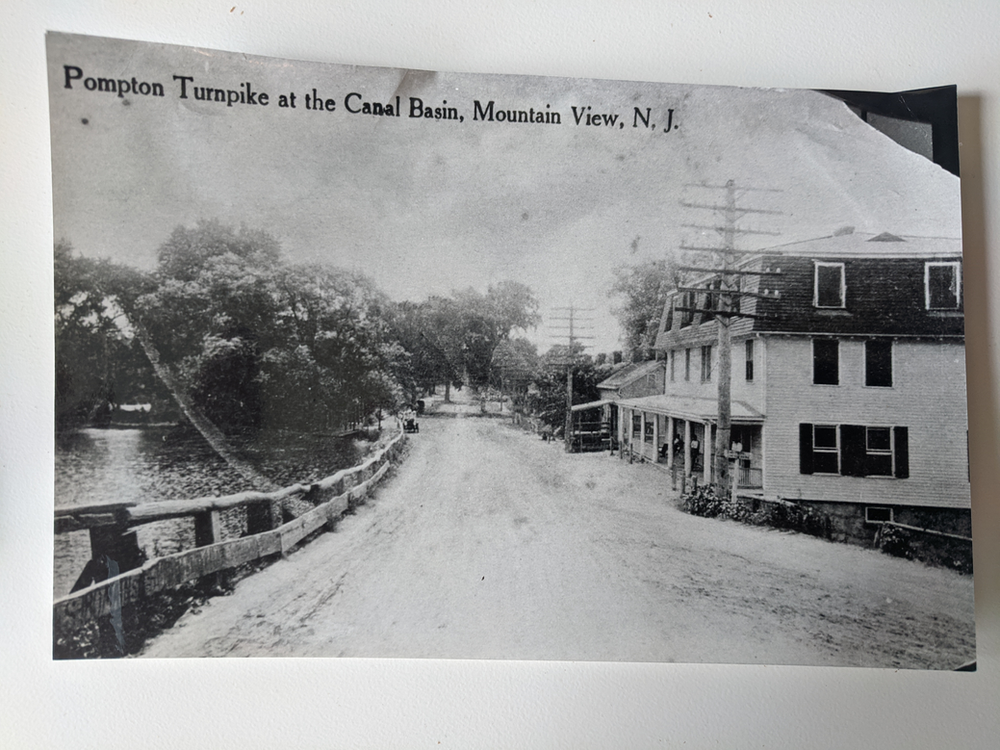

Though the Mead-Van Duyne House sits behind the Van Riper-Hopper House today, its 1870s location was on the corner of Fairfield Road and what would become Route 2, labelled as P. Van Done’s home. The home’s original location, right in the middle of the Mead’s Basin, later Mountain View, area, was once a hub of activity. It was near two railroads, the Morris Canal, and the Pompton River. Residents of the home would have been used to the hustle and bustle of travelers passing through, and the businesses that cropped up to cater to them; hotels, general stores, restaurants, and more. Though George Catlin described Mountain View in 1873 as “a small and unpretentious [village]”, it was the closest Wayne got to an ‘urban’ area.

Only about ten years before the atlas was published, Reverend Edward Payson Terhune purchased several acres of land along Pompton Lake for $600; his wife, Mary Virginia Hawes, would describe the property as “a shimmering sunset lake and a natural stretch of shining green lawn.” By 1877, the couple’s acreage grew to 25 acres, and they’d built a three-story Victorian home, featuring a central gable, attic, cellar, and extensive veranda, named Sunnybank. In 1877, Sunnybank was a seasonal home for the family, including children Christine, Virginia, and five-year old Albert Payson, who would go on to memorialize the site in his books about collies. While the home was demolished later in the 20th century, the property is designated as Terhune Memorial Park. Terhune and Sunnybank artifacts remain on view at the Van Riper-Hopper House.

The map also notes the presence of several local institutions. By the 1870s, Preakness Reformed Church was a well-established center for the community, having been rebuilt about 20 years prior. George W. Labaw describes the structure, ca. 1902, as “a commodious, neat, and substantial structure” with 60 pews and “an exceedingly handsome solid mahogany pulpit.” He adds that “the church also at first was lighted for evening gatherings by candle brackets, or candelabra, which were of bronze, and handsome in pattern or style.” In early May 1930, a fire broke out, completely gutting the building. However, church members decided to rebuilt on the same site, integrating the remaining walls and foundations and remaining in close proximity to the historic cemetery. Preakness Reformed Church’s current structure was completed in 1931, preserving the historic spot on Church Lane.

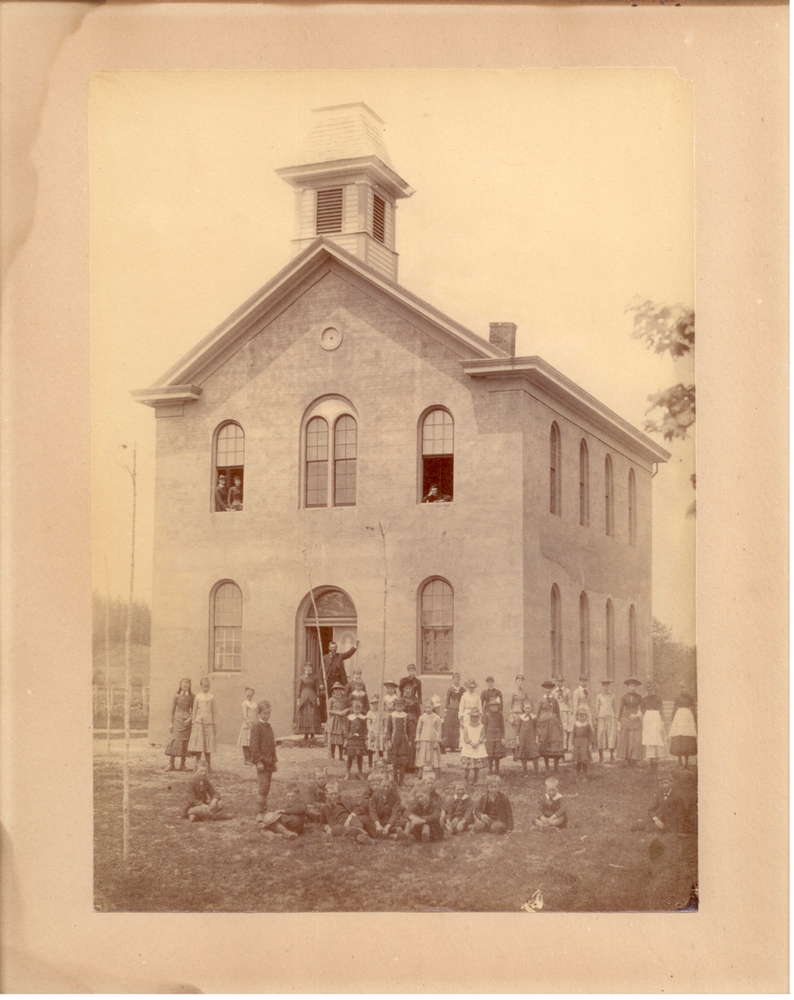

Figure 11- Two local institutions in Wayne Township- the Upper Preakness School on Hamburg Turnpike (photographed ca. 1880) and Preakness Reformed Church on Church Lane (photographed before the 1930 fire). Both photos from the Wayne Museum.

Though Wayne would have five elementary schools by the end of the 19th century, this map only notes four. Down the street from the Preakness Reformed Church sits what would become the Upper Preakness School, No. 14, while No. 13, the Mountain View School, is likely the one noted close to the Mead-Van Duyne House. As of 1877, these two schools were probably one-story, even one room, schoolhouses. The Upper Preakness School was expanded into a two-story building, which survives today and houses Wayne Counseling and Family Services, ca. 1880. A two-room schoolhouse was built for the Mountain View School on the 1877 site ca. 1890, though the school was later moved to a three-story brick building constructed in 1920. Today, Mountain View’s original schoolhouse survives, somewhat modified, as the home of the Anthony Wayne Post of the American Legion.

While the Wayne of 1877 had not reached the development heights that we see today, that does not mean it was a completely isolated, rural township. Besides individual properties, many of which were run as truck and home farms, the 1877 map notes various businesses in Wayne; some agriculture based, some more industrial. Two mills and three brickyards are specifically labelled; in Images of America: Wayne Township, Cathy Tobin writes that “at least six brickyards were in active operation in Wayne between 1870 and 1930. An average day during the busy season of May through October yielded 30,000 bricks in 1882.” Larger agricultural centers, like J. Greive’s Green Brook Farm and Milton Sanford’s Preakness Farms (and race-track) can be seen as well. From the 1860s to the early 20th century, Wayne was frequently rocked by the Laflin & Rand Powder Company and the Rend Rock Powder Works, which manufactured gunpowder and explosives. Explosive accidents throughout the late 19th century were often reported on in the local newspapers, shaking Wayne and heard as far away as Morristown and Newark.

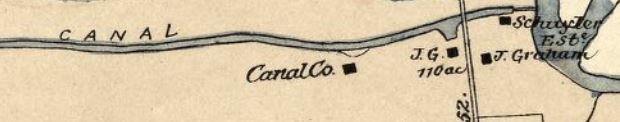

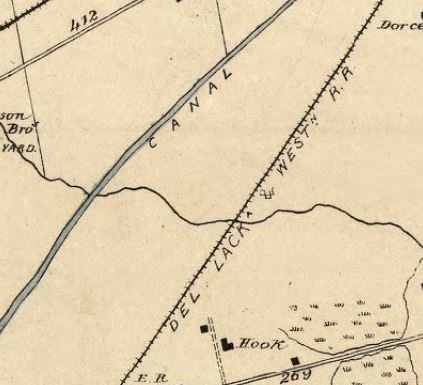

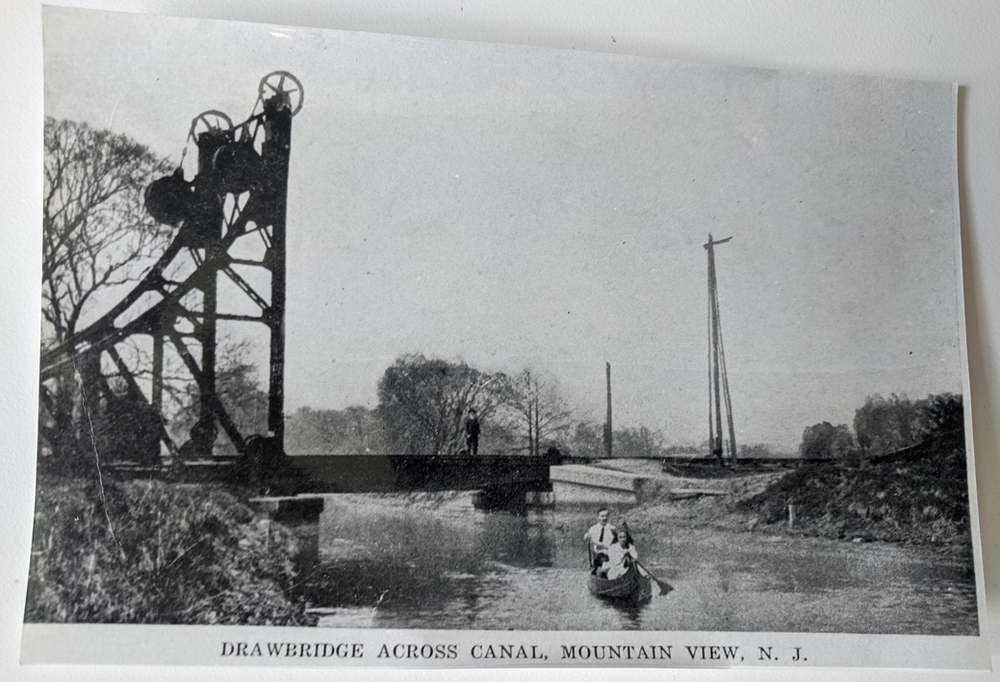

The Atlas also illustrates Wayne’s developing transportation routes. The Paterson-Hamburg Turnpike and Newark-Pompton Turnpike were both incorporated in 1806 as toll roads; Tobin writes that “wagons were charged 1 cent per mile per horse (up to four horses), and a horse and rider were charged ½ cent per mile.” The Morris Canal, first opened in 1832 to link coal mines in Pennsylvania with industrializing regions in New Jersey and New York, also ran through Wayne. This stimulated the development of Mead’s Basin (later Mountain View), with hotels, stores, and other businesses popping up to cater to travelers. By 1877, the canal was declining in popularity, particularly due to the growth of railroads. As seen on the map, the Delaware, Lackawanna, and Western Railroad and the Montclair and Greenwood Lake Railroad passed through Wayne, connecting residents to Jersey City, Montclair, and further locales, like Pennsylvania and upstate New York. In later years, the Delaware, Lackawanna, and Western Railroad would even include connections to New York City, Detroit, Cleveland, and Chicago.

Figure 11- Scenes of transportation in Wayne Township- the Morris Canal, railroad lines, and the Mountain View Train Station. All images from the Wayne Museum. Atlas clippings from from the “Atlas of Passaic County, New Jersey.” From the Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3813pm.gla00164/?sp=45.

The 1877 map of Wayne included in the Atlas of Passaic County reveals a township quite different from the one we experience today. Though it was not completely isolated- roads, railroads, and canals connected the township to the rest of New Jersey and beyond- Wayne was still largely rural. Land now filled with bustling shopping centers, busy roads, apartment complexes and family homes was once occupied by family farms, swaths of pastures, and crops ready to harvest. As we continue to study older maps of Wayne, we can further understand the history of the township, and how it developed into the busy community we see today.

Bibliography

For further information about Wayne’s farming landscape, check out our November 2022 ‘This Month in Wayne History’ article, which discusses the area that became Point View Reservoir.

Berce, William. Under the Sign of the Eagle. Wayne: Louis J. Vorgetts, 1965.

February 1965. Interview with Bertha Hopper, Mr. Mott, and Rita Rehers. From the Wayne Museum.

Labaw, George Warne. Preakness and the Preakness Reformed Church. Volume I. New York: Board of Publication of the Reformed Church in America, 1902

Smith, Albert A. Preakness and the Preakness Reformed Church: A History. Volume II. Wayne: Preakness Reformed Church, 1992.

Rauchfuss, William H. “A Visit To The Dawes House,” Paterson Evening News (Paterson, NJ), February 2nd, 1935.

Catlin, George. Homes on the Montclair railway, for New York businessmen. New York: Montclair Railway Co, 1873.

Kathleen Rais MacMurray. “And We Will Name It ‘Sunnybank’!” The Lookout (Fall/Winter 2013).

Tobin, Cathy. Images of America: Wayne Township. Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 2001.

“Explore the Morris Canal,” Canal Society of New Jersey. Accessed December 7th, 2022. Morris Canal – Canal Society of New Jersey (canalsocietynj.org).

Burns, Adam. “Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad (DL&W): ‘The Route of Phoebe Snow.’” American Rails. December 10th, 2021. Accessed December 7th, 2022. https://www.american-rails.com/dlw.html.

“A Short History of the New York & Greenwood Lake Railroad.” Montclair State University. Accessed December 7th, 2022. https://msuweb.montclair.edu/~olsenk/M&GL.html.