Getting to Know Hester Schuyler Colfax

By: Tessa Payer, Museum Specialist at the Wayne Museum and Staff Member of the Passaic County Department of Cultural & Historic Affairs

"One story in particular, which Mrs. Comstock remembers was told of her grandmother, was that one day the general bought her a new shawl which displeased her. Promptly she threw the shawl in a kettle of hot water on the stove and permitted it to boil unforgotten as she flung herself out of the room." [1]

Beautiful, tempestuous, and haughty are only some of the words that have been used to describe Hester Schuyler (1757-1839), who inherited the Schuyler-Colfax House following her father's death in 1795. In 1974, Paterson's The News described her as "a very beautiful and spirited young woman," while she appears as "a black-eyed girl/of roguish witchery" in Charles C. Platt's 1896 poem "Capt. Colfax and the Life Guard." Unfortunately, none of Hester's own writings survive, leaving us with only others' descriptions of this 18th century heiress. Today, we're combining recollections and archival records to see what we can learn about the life and personality of Hester Schuyler.

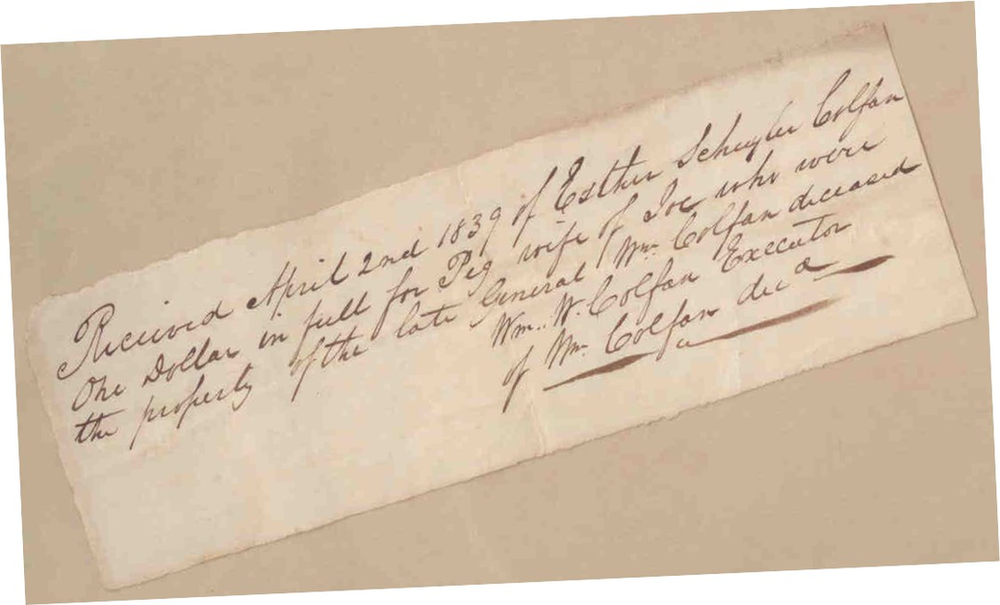

As a note, even Hester's name is up for some debate! We've seen both 'Esther' and 'Hester' used in documents from her lifetime. Most secondary sources and family recollections refer to her as Hester, which is how we will be referring to her in this article.

Hester, born in 1757, was the only surviving child of Casparus Schuyler and Christina Ryerson. Both her parents brought well-known family names and lineages to their marriage. The Ryersons were a prominent local family; Alfred Ryerson, in his book The Ryerson Genealogy, described Christina's father, Martin Ryerson, as "a man of sound judgement, and keen business sagacity. This is evidenced by the large estate which he distributed among his daughters and their children." [2] On the paternal side, the Schuylers had been making waves in Wayne since Hester's great-grandfather, Arent Schuyler, led negotiations with members of the Munsee Lenape for the 1695 land sale that would define Wayne's general acreage. The Schuyler-Colfax House, where Hester grew up, had been built under her great-grandfather's purview around 1696 and had since housed members of the colonial legislature and Bergen County freeholders. Since the 1690s, the family had accumulated wealth from the Pompton Ironworks as well as their own land, which they developed as a farm supported by the labor of enslaved people.

Little is known about Hester's childhood, but it can be assumed that she was raised in privilege at the Schuyler-Colfax House. Her family's wealth may have afforded her a full education, perhaps comparable to her distant Schuyler cousins in Albany, New York, who studied writing, mathematics, geography, history, and foreign languages alongside needlework, drawing, music, and dancing. [3] From her mother, Hester would have learned how to manage the Schuyler household, overseeing numerous daily tasks- cooking, cleaning, sewing, agricultural labor, and more- that kept the Schuyler estate running. She was no stranger to enslavement, as it was African Americans owned by her father who completed this litany of daily activities. By the time she reached her majority, Hester likely had an enslaved maid who helped her to dress, style her hair, and accompanied her throughout the day; her granddaughter, Annie Comstock, would remember that "never in all the years of her life did [Hester] comb her own hair. This as well as the other duties of the home was taken care of by slaves." [4] For Hester, those enslaved by her family were an integral part of their material wealth, and others would recall how she incorporated enslaved people into her personal display. In his book Under the Sign of the Eagle, William Berce paints a vivid picture of Hester's fashionable display and her involvement of enslaved people:

"Once at church, the entire congregation would turn towards her in admiration and envy as she walked down the aisle to her pew- her train of fine, imported silk held aloft by one of the slaves while the other carried a footwarmer or fan- according to the season." [5]

Comstock also shared a similar memory of her grandmother, gown train held aloft by an enslaved child as "she swept down the church aisle." [6] Both descriptions certainly suggest a Hester Schuyler who was proud of her wealth, privilege, and status as an enslaver, and was more than willing to display both in a public setting, asserting her status in local society.

When the American Revolution broke out in 1776, Hester was at the end of her teen years, and, from all accounts, had matured into a young woman sure of her family standing and her own status as her father's sole heir. Whether she truly boasted the "bewitching dark eyes and long, raven hair" that William Berce describes her as having is uncertain, as only a silhouette of Hester survives in the Wayne Museum's collection. [7] Whatever her looks, it was not quite an exaggeration for Berce to describe Hester as "proud, cultured, [and] influential" and these qualities soon caught the attention of one of the Continental Army officers who spent July 1780 residing at the home of Hester's aunt, the Dey Mansion. [8]

It's easy to romanticize the courtship of William Colfax, the dashing member of George Washington's guard who would soon be promoted to Captain, and Hester Schuyler, the heiress. Theirs was one of countless wartime romances- similar to that of Alexander Hamilton and Hester's distant cousin, Elizabeth Schuyler, who were married in the winter of 1780. After their initial meeting in the summer of 1780, Hester and William were reunited that fall, when the Continental Army returned to Wayne, and Washington once again took up residence at the Dey Mansion. William followed Washington to Virginia, where he was present for the Battle of Yorktown, before he returned to New Jersey for his marriage to Hester on August 27th, 1783. [9] As Charles C. Platt rhapsodized, "And when he laid his sword aside/In seventeen-eighty-three/To Pompton Plains he came anon…And there fair Hester won the day/She conquered, yet did yield/And Captain Colfax led his bridge/In triumph from the field." [10]

The couple moved into Hester's family home in Wayne, giving the property its modern name, the Schuyler-Colfax House. It was likely during their residency that the fashionable two-story, four bay structure was added onto the initial one-story home, providing more space for entertainment and for their family. Hester and William had six children, and William's political involvement- he was a county justice of the peace, a delegate to the state General Assembly, served on the Legislative Council, and led a brigade of New Jersey militiamen during the War of 1812, for which he was appointed a General- likely kept the family well occupied with guests. [11] Hester, as her mother once had, would have overseen preparation for guests and directed the daily labor of those enslaved by the family. Though the exact number of African Americans enslaved by the Colfax family is unknown, the Wayne Museum has eight surviving bills of sale that record William and Hester's purchase of enslaved adults and children. Between the 1790s and the 1830s, William purchased Sam, Bob, Cuff, Pero, Nelly and her child, Prince (or Touseant), and Phebe. While many of these individuals likely labored on the Colfax farm, Hester would have overseen those involved in domestic work. In 1839, following her husband's death, she purchased "Peg wife of Joe" from his estate; perhaps Peg served as her personal maid? [12]

The Schuyler-Colfax marriage, however, was not the romantic triumph that Platt alluded to. Later recollections point to conflict between Hester and William, such as the dramatic fight over the shawl that Annie Comstock remembered in 1926. Both The News and William Berce noted the story of a temperamental Hester leaving the Schuyler-Colfax House for church services without her husband, leaving him to catch up to her carriage. [13] Berce also adds, "family tradition tells of one occasion when Hester, highly incensed over one of Colfax's business ventures, exploded with, 'I had my choice of ten generals and I picked you- the worst of the lot!'" [14]

William's handling of the family finances seems to have been the root of the couple's conflicts. According to Berce, "Colfax had limited sagacity or shrewdness when it came to making money" as well as "an overwhelming generosity which never denied the need of a neighbor or friend." [15] The estate inventory taken after William's 1838 death, which is now in the Wayne Museum's collection, corroborates these statements. The last eight pages of the inventory list the individuals who William loaned money to; many are listed as doubtful or desperate, suggesting that they would not be repaid." [16]

Her husband's apparent mismanagement of their money may have particularly upset Hester given her legal status before her marriage. As her father's sole heir, she was due to inherit his full estate, which included the Schuyler-Colfax House, farmland, money, material belongings, enslaved people, and more. However, when she married, control of this property passed to William under the legal principle of coverture; as William Blackstone wrote in his Commentaries on English Law, "by marriage, the husband and wife as one person in the law; that is, the very being or legal existence of the woman is suspended during the marriage, or at least is incorporated and consolidated into that of the husband." [17] While Hester retained rights to her inherited real property- her family home and land- William could still use the land and had legal control of the family finances. This loss of control, especially over property and money that had once been hers, likely contributed to the conflict between the county as well as Hester's tempestuous reputation.

William Colfax died in 1838, and Hester followed him a year later. She was buried under a gravestone reading "Hester Schuyler- Wife of General William Colfax"; a simple epitaph for a woman with an apparently large personality. While she did not leave behind her own words, the recollections of her family members and later writers paint a picture of a strong-willed woman born into a life of privilege, who strove to maintain that status throughout her life.

The Wayne Museum operates under a shared services agreement between the Township of Wayne and the County of Passaic. The County manages and operates the Wayne Museum on the Township's behalf through the County's Department of Cultural & Historic Affairs.

Notes

-

"Mrs. Annie Comstock At Ninety Gives Recipe For Long Life," The Paterson Morning Call, September 23rd, 1926.

-

Ryerson, Albert Winslow. The Ryerson Genealogy. Edited by Alfred L. Holman. Chicago: 1916. 23.

-

Serfilippi, Jessie. "'I shall most cheerfully pay': The Education of Caty Schuyler." Schuyler Mansion State Historic site (blog). March 28th, 2020. Accessed February 24th, 2023. https://schuylermansion.blogspot.com/2020/03/i-shall-most-cheerfully-pay-education.html.

-

"Mrs. Annie Comstock At Ninety Gives Recipe For Long Life," The Paterson Morning Call, September 23rd, 1926.

-

Berce, William. Under the Sign of the Eagle. Wayne: Louis J. Vorgetts, 1965. 196-197.

-

"Mrs. Annie Comstock At Ninety Gives Recipe For Long Life," The Paterson Morning Call, September 23rd, 1926.

-

Berce, 186.

-

Ibid.

-

"New Jersey Colonial Documents- Marriage Licenses." Ancestry.com. New Jersey, U.S., Marriage Records, 1683-1802 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011. 367.

-

"Ballad of Captain Colfax." Pequannock Township. Accessed February 24th, 2023. https://www.peqtwp.org/249/Ballad-Of-Captain-Colfax.

-

Berce, 197.

-

Colfax, William W. and Esther Schuyler Colfax. "Bill of Sale for Peg wife of Joe, April 2nd, 1839." Bill of Sale. From the Wayne Museum.

-

Berce, 196; "Memories Abound in Colfax Home." The News, May 9th, 1974.

-

Berce, 196.

-

Ibid.

-

"A true and perfect inventory of all and singular the goods and chattels rights and credits of William Colfax late of Pompton in the township of Manchester in the County of Passaic and State of New Jersey deceased, September 20th-22nd, 1838." Estate Inventory. From the Wayne Museum.

-

Salmon, Marylynn. "The Legal Status of Women, 1776-1830." The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History: AP US History Study Guide. Accessed February 24th, 2023. https://ap.gilderlehrman.org/essay/legal-status-women-1776%C3%A2%E2%82%AC%E2%80%9C1830#:~:text=So%20long%20as%20they%20remained,changes%20in%20women's%20inheritance%20rights..