Artifact Analysis: A Mid-19th Century Chemise

By: Tessa Payer, Museum Specialist at the Wayne Museum and the Passaic County Department of Cultural & Historic Affairs

Today is National Textiles Day- the perfect occasion to spotlight our clothing and textiles collection! We’re very lucky to have some fantastic pieces- Victorian mourning bodices, turn of the century shirtwaists, mid-19th century skirts, wedding gowns, and more.

However, today, I’ll be introducing you to a less eye-catching piece from our collection- a chemise- and exploring what the simple chemise can tell us about women’s clothing and experiences in the 19th century.

To give a basic description, the chemise looks like a short dress. It is made of lightweight white fabric, probably linen or cotton. It has a wide neckline and short sleeves, but is otherwise loose-fitting. It fastens in the back with a single button. All the stitching appears to have been done by hand. From the shoulder to the hem, the chemise measures about 36 inches.

So, what is a chemise? It was one of the basic undergarments of the 19th century, worn by a woman every day. Like wearing a pair of underwear today, the chemise would have been the first layer, followed up by a series of other undergarments. It was an almost universal experience for women at the time. Women at opposite ends of the social and economic spectrum started their days by slipping on a chemise; though their choice of clothing probably diverged from there.

Based on the hand-sewn construction and silhouette, we’ve dated this chemise to the 1850s. Like any other decade, the 1850s had a favored silhouette, which any fashionable woman (or women who could afford to be fashionable) aspired to; a triangle set atop a bell, with sloping shoulders, a narrow waist, and full skirts. Besides its practical use as an undergarment, the chemise also played a part in creating this stylish silhouette.

Imagine- you’ve slipped on your chemise, but there’s much more to go! Next came a pair of stockings, tied onto the legs by a set of garters or ribbons before the invention of elastic allowed for more tight-fitting socks. Then came drawers, loose fitting pants that were often split at the crotch; this feature answers the infamous question, “how did they use the bathroom in all those layers?”

The corset followed. It’s a divisive garment today; was it a necessary part of women’s everyday wear, or an oppressive piece of clothing that confined women’s bodies? In reality, the corset falls somewhere in the middle. While increased boning and lacing helped to create the fashionable body shape of the mid-19th century, corsets provided back and bust support- and supporting the weight of the layers to come. Fashion historian Nicole Rudolph describes corsets as “the interaction between a woman’s body and her garments, making sure they functioned well together and that the fashionable shape was achieved but also that a woman could function and do what she needed to do on a daily basis.” Like the chemise, most women in the 1850s wore some form of a support garment, like a corset. However, not all corsets of the period were the same; fabric choices and boning could depend on what a woman could afford, or the work she did day to day. A corset might be followed up with a corset cover; like the chemise, but shorter, this protected both the corset and outer layers from wear and tear.

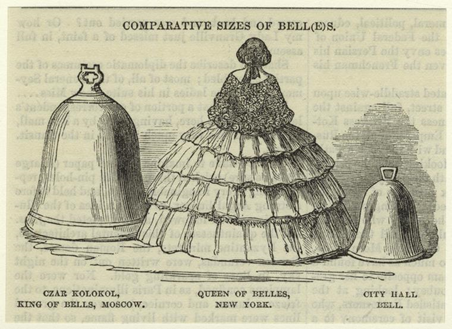

As I noted earlier, the fashionable silhouette of the 1850s was a triangle set on top of a bell. The chemise’s open neckline accommodated the shoulder slope, the corset smoothed the waist, but a woman’s bottom half required further shaping. To achieve the bell shape, women layered petticoats one on top of the other, wearing as many as eight at one time. (You can now see why a corset’s support might be useful). Often, the petticoats were tiered with layers of flounces, or stiffened with channels filled with horsehair, scrap fabric, and even whalebone. The term ‘crinoline’ was introduced to describe the stiffened fabric used to make these petticoats. Wider skirts also provided the illusion of a smaller waist.

However, our chemise may have been witness to an exciting transition in the fashion world; the invention of the cage crinoline. As the 1850s went on, crinoline petticoats could no longer support the growing trend (literally) for wider skirts. In 1856, the cage crinoline was patented; a garment consisting of hoops made of whalebone, cane, or steel sewn together by cloth tapes. The cage crinoline’s hoops grew wider and wider as they reached the hem. With only one or two petticoats draped over, the cage crinoline provided a lightweight way to reach the fashionable shape.

Now, about six layers after the chemise, we’ve finally reached the outer layers, from plainer day bodices and skirts to silk evening gowns. However, even with the distance between the two layers, the chemise played an important role in the protection of outer garments. It was the first clothing item to come into contact with the body, absorbing sweat and body oils and keeping them from damaging outerwear. A chemise like ours would have been washed frequently and was made to withstand such treatment. Wearing a chemise meant that more fragile and complex garments, like bodices and dresses, did not need to be fully washed, only spot cleaned. Protected from bodily stains and the damage of frequent washing, the expensive fabrics that made up outerwear lasted longer and could be re-used.

In The History of Underclothes, authors C. Willett and Phillis Cunnington describe a ca. 1849 chemise, similar to the one in our collection, and note that “the severe plainness of the day garment is characteristic of an article entirely concealed from view.” Though it was often hidden from view, the chemise was incredibly important to the female wearer of the mid-19th century. It was the first layer of the day, and a protective barrier that helped to maintain outerwear. By studying the chemise, and 19th century clothing layers, we can learn about the lived experience of women in the period and get a taste for walking in their shoes (or their chemise).

The Wayne Museum operates under a shared services agreement between the Township of Wayne and the County of Passaic. The County manages and operates the Wayne Museum on the Township’s behalf through the County’s Department of Cultural & Historic Affairs.

General Bibliography

“Corsets, crinolines and bustles: fashionable Victorian underwear,” V&A. Accessed April 9th, 2023. https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/corsets-crinolines-and-bustles-fashionable-victorian-underwear.

“Shift,” V&A. Accessed April 9th, 2023. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O327719/shift-and-sleeve-unknown/shift-unknown/.

“Women’s Fashion in the 19th Century,” Historic Hudson Valley. Accessed April 9th, 2023. https://hudsonvalley.org/article/womens-fashion-in-the-19th-century/.

Glasscock, Jessica. “Nineteenth-Century Silhouette and Support.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/19sil/hd_19sil.htm (October 2004).

Willet, W. and Phillis Cunnington. The History of Underclothes. New York: Dover Publications Inc, 1992.

Nicole Rudolph. “100 Years of Corset History: How 8 Corsets affect the same body.” YouTube. November 29th, 2020. Accessed April 19th, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZzKUI0TwgFM.

Dealy, Anne. “19th-Century Corsets.” Historic Geneva. November 12th, 2020. Accessed April 19th, 2023. https://historicgeneva.org/fashion-and-clothing/19th-century-corsets/.

Bach, Emily. “Corset Covers: Protection Against Soiling and Indecency.” MDHistory. Accessed April 19th, 2023. https://www.mdhistory.org/corset-covers-protection-against-soiling-and-indecency/#:~:text=Corset%20covers%20began%20to%20appear,specific%20occasion%20it%20was%20worn.