All that Glitters: The Coming-Out Party of Mae Anderson Bell

Hannah Rodums, Museum Attendant at the Wayne Museum and Passaic County Department of Cultural & Historic Affairs

As she stands by her mother’s side on the night of the dance that is given to introduce her to society, she is a vision of girlish loveliness all in white.

– “Debutante Now Holds Social Stage’s Centre”, The Morning Call, 1915

ONE-HUNDRED and thirty-two years ago, on a cold, snowy December night, the peal of laughter and the sound of Christmas carols rang through the streets of Paterson. The cause for such celebration? Miss Mae Anderson Bell, one of Paterson’s “fairest daughters”[1], made her grand appearance to dozens of the city’s most elite and distinguished citizens—the first debutante of her caliber the city had seen in many years. Upon stepping into the parlor in her family’s mansion that evening, Miss Bell was no longer considered a child, but a lady: and, as a lady, she was now welcome to enjoy all the riches and splendor Paterson’s “Four Hundred” club had to offer.

Join us this month as we peek behind the curtain at Mae’s coming-out party: a lavish coming-of-age celebration held for the daughters of fabulously rich and powerful American families, specifically at the turn of the 20th century. Usually between 17 and 18 years old, young women like Mae had been presented at society functions for over a century by the time of her own debut. Many a debutante viewed her “coming-out” with a mixed bag of anticipation and trepidation: the defining event of her young life that declared her physical and emotional maturity to the world, now eligible to be courted by young men of the same or greater social pedigree. In doing so, she stepped out of the protective shadow of her parents’ wings—and into a world that was as enthralling as it was constricting.

~

THE “SEASON”, as it’s called, starts in November, after the American elite have returned from their summer homes in the country to their residences in the likes of New York, Boston, Washington, and Chicago. The weeks before and after Thanksgiving are dedicated to “coming-out” parties, usually in the form of an afternoon tea. Teas, in fact, are so common amongst the rich one young lady likens her debut to being “brought, like all the other raw recruits, upon tea and toast”[2]—the product of a great many young women being introduced within days, if not hours of each other. After she comes out, the debutante is whisked away on a whirlwind tour of society throughout Christmas and the New Year, introduced to every form of nightlife and entertainment that can be had. The season officially closes with the onset of Lent—before picking up again with another class of debutantes the following November.

For the average woman living in Wayne, Totowa, and other north Jersey towns, newspaper coverage of these teas provide a tantalizing glimpse into the celebrity world of the rich. Debutantes, according to the press, are exquisitely beautiful for their age—most often tall and slender, “divinely fair”[3] in complexion, with blond or light brown hair and “perfectly regular features”[4]. (Mae herself is described as “charming” and “handsome” in the Paterson Evening News). The attention the young women receive is due in no small part due to their fathers: being the daughters of industry heads, ambassadors, politicians, supreme justices, even former and current presidents of the United States[5]. It comes as no surprise then that they are well-educated—having graduated college at the top of their class[6], or, in other cases, attaining their educational pedigree through long stays in Europe or by virtue of the social circles their parents walk in. Some debutantes are even noted for their athletic pursuits. From horseback riding to cycling through city streets[7], the American debutante is just as physically fit as she is attractive.

Character is another focal point. America’s sweetheart debutante may enjoy handling a rifle, or swimming, or playing football[8] in her spare time, but the reporters are very careful to state that her feminine charm isn’t diminished by participating in such “manly” activities. Such overt signs of masculinity are smothered in apologies and appeals to the lady’s true, gentle disposition—like in the case of Miss Violet Sibyl Pauncefote, a prospective debutante of 1891 who loved to walk:

Let no one suppose from this description that Miss Pauncefote is masculine; she is not; quite the contrary. She is modest and sweet as the dainty English blossom whose name she bears.[9]

Most becoming to the press is a debutante with the personality of a dove: “a wholesome, unaffected girl, who meets all with a frank cordiality that is very winning”[10]. Never mind if she “prefer[s] athletic sports to the pleasures of the drawing room”—no matter how intelligent, talented, or athletic she is, she must learn to “accept her position with quiet dignity”[11] within the confines of the parlor and the tearoom. It is, as the papers say, only proper for her. “Beauty, style, and grace in dancing are the most important assets of the debutante.”[12]

The guest list for Mae’s coming-out is long: encompassing a select group of Mae’s friends (who will assist Mae and her mother in receiving said guests), as well as a host of family friends, acquaintances, and the many professional contacts Mr. and Mrs. Bell have made within their social circles. It is also carefully curated. Mrs. Bell has been especially diligent in inviting guests she believes are in good standing with the rest of polite society. People talk in the Four Hundred: it would not look well for her if she invited a close relative who is rumored to have squandered his wealth gambling. Nor would it be good for Mae, on the cusp of entering society, to be spotted talking to a friend with a dubious reputation—be it from her own life choices or the choices of her immediate family. Any other young women invited to the party will be required to come with their mothers, or perhaps a maid if the mother cannot come—decorum insists young women be attended by a chaperone for large social functions. People Mr. and Mrs. Bell do not know are not invited. One bad apple, they say, doesn’t spoil the whole bunch—but it does make a person pause before picking out of the same basket.

Meanwhile, Mr. Bell has spared no expense in putting together the finest party for his only daughter. Food for the guests must be catered—sandwiches, cakes, bouillon, and salad, with tea, coffee, and lemonade[13] for drinks, all chosen by Mrs. Bell. The house must be decorated accordingly, covered from floor to ceiling with flowers—white lilies to represent innocence and purity, red and pink carnations for love, sweet-smelling roses to inundate the room with their perfume, offset by palms and greenbrier for greenery. Musicians must be hired for ambiance—they will be hidden behind a screen, or tucked away in a far-off nook, as not to detract from the scene[14]. Even with the spacious proportions of the Bell mansion, stuffing the band, banquet, and bower into its first-floor rooms may prove too big a task. In such cases, Mr. Bell may be inclined to host the event at a hotel ballroom instead—a fine arrangement for the hotel, as they draw in thousands of dollars revenue during the “coming-out” season from men like him[15].

Mae will also need to spend a pretty penny to keep up with the demands of the world she is being sworn into. Now that she’s a woman, she’ll have to replace her entire wardrobe with dresses and gowns appropriate for her age. She’s also aware that a debutante, rightly or wrongly, is often judged by how she looks[16]. Anything gaudy will draw accusations of her being self-absorbed and frivolous with her father’s money; anything too modest, however, will make her look either miserly or poor, and at the very least out of touch with the latest fashions. Therefore, months ahead of her formal debut, she and Mrs. Bell have spent countless hours at local shops and modistes, having clothing specially made for her. Pale colors and simple styles are the rule for young ladies just coming out—the brighter jewel tones and elaborate fabrics being reserved for married and older women. Papa’s purse strings also come in handy[17]. Mae will be known amongst her peers for having the finest dresses in the finest fabrics around if she’s allowed to spend a little—never mind having a father with that much money to shower over her.

Behind the scenes, Mae has been rigorously training for her coming-out. She’s learned how to walk—and dance—in high-heeled pumps. For a few hours each night, she swaps her regular clothes for a gown with a low neckline and no sleeves. Society functions such as balls and operas permit women to wear short-sleeved (sometimes sleeveless) evening gowns, complete with plunging necklines that reveal a fair amount of shoulders and bosom—a style Mae has seen, but never worn herself. Therefore, she must learn to become comfortable with exposing her shoulders and breasts in a way she’s never done previously. Her diet consists of beef tea and light meals such as oatmeal and chicken salad; she must be careful to take lunch at the same time of day to maintain her weight[18]. For the moment she rises at seven in the morning and retires between nine and ten o’clock at night. This, among other things, will dramatically change after she comes out.

Reporters for The News attend Mae’s coming-out the night of December 19, 1891. They will bring to life the extravagance and ostentatiousness of her big debut for the reading public—from the Hopper girls on their farm in Preakness to the Mead daughters down in Mountainview.

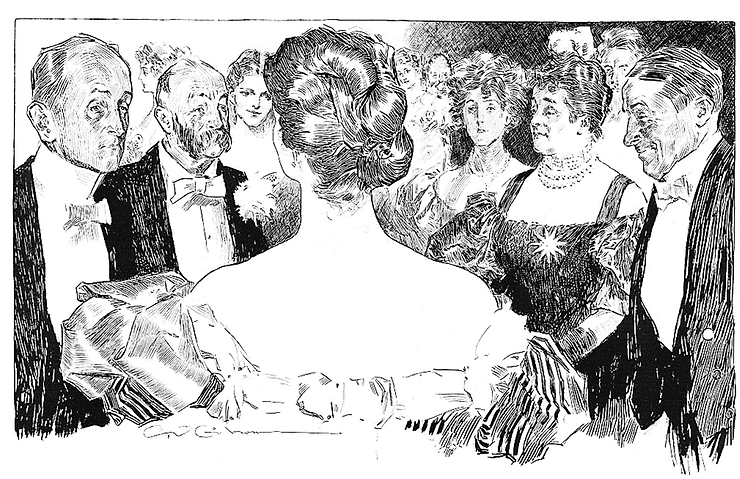

The traffic outside the Bell mansion, for one, is a nightmare—a sea of carriages, coaches, and hansoms clogging up the intersection of Broadway and Carroll Street, waiting for their turn to pull up to the curb and unload their passengers. Tonight, Paterson’s Four Hundred are dressed in their finest: the men dressed in white tie, some with long coattails, others in dinner jackets; the married women in magnificent gowns “worthy of Worth”[19], made of richly colored velvets, crepes, and silk brocades, adorned with lace and jewelry. Upon entering each is instructed to leave their coats and cloaks in the appropriate dressing-room specially attended to by a servant—space is tight, after all—before entering the drawing room.

Every room in the Bell mansion is “a veritable bower”[20] of flowers. Large bunches of mums, white roses, and hyacinths hang from the chandeliers. Further down the hall stands “an arch of smilax [greenbrier] and carnations supported by solid columns of flowers”. Garlands of braided greenbrier, roses and palms run along bookcases and fireplace mantels. In the drawing room, the interior designer saves his finest work for last: every window is draped with a “curtain” of greenbrier vines, tied back with large white bows, the same decoration festooning a large floor-to-ceiling mirror. It is a dream come to life; a fantasyland specifically designed for the fairy princess who inhabits it.

Over by the drawing-room the door Mae stands between her parents, as they greet each guest who files in. Mae’s dress, according to tradition, is white and “oh, so, simple”[21]: made of satin or silk, chiffon and tulle, featuring a low-cut neck and short sleeves. She wears no jewelry save a thin strand of pearls about her neck, and covers her arms with long gloves of white kid. It took over two hours for her maids to do up her hair and dress her—polishing her arms and neck with a mixture of glycerin soap and rose water, to shimmer under the gas lights[22]. Her bare shoulders and bosom, naturally, are on display for everyone to see. One can only imagine what Mae thinks as she stands like a porcelain doll in a toy store, blushing to the “oohs” and “ahhs” of a crowd of strangers as they gaze upon her[23]. She is the center of everyone’s attention—and for better or worse, she knows it.

After an hour Mae’s friends are free to leave the line of receivers to do what they like—they may have other receptions to attend. Mae however must stand with her parents until the last guest has arrived—shaking the hand of every man and woman who stops to congratulate her, listening patiently as her mother introduces them. Her arms will be heavy from all the bouquets her guests have given her: decorum frowns upon more than two, but for a popular young woman like Mae, she may well end up with eight, ten, or even a dozen bouquets from friends and well-wishers by the end of the night. Each bouquet received is not just a reflection of admiration for Mae, but also a subtle commentary on her father’s wealth. It is his money, after all, that has been spent creating his daughter’s fairytale garden. So, if upon receiving yet another bouquet, Mae exclaims:

“No fewer than eight bouquets—just think of it! Are they not lovely?”

The giver of that bouquet may simply reply with a wink: “Yes. Lovely, indeed. And how good of your papa.”[24]

After dinner the festivities turn to dancing in the mansion’s entertainment parlor. Mrs. Bell, ever prepared, has already arranged the first young man Mae will ever dance with—usually a close family friend, with whom Mae is familiar. After they dance, any man in the room is welcome to ask for Mae’s hand for the next one. Here Mae must be careful—she can refuse a dance with someone, with the caveat that if she does, she’s not allowed to dance with anyone else for the duration of that particular dance[25]. She will have to sit out and wait for the next dance to start. Meanwhile Mr. and Mrs. Bell walk about the room, pairing guests with dancing partners if they have none, coaxing the diffident and unsociable out of their hiding places and encouraging them to mingle with the party. Everything must go according to plan, every guest on their best behavior—be they busybodies or wallflowers.

Mae will head off to bed in the wee hours of the morning, tired no doubt, or perhaps a bit jittery from the emotions still running fresh in her mind. She has a busy day ahead: three of her friends will be coming-out tomorrow afternoon, not to mention she’s been invited to her very first dinner party, and a ball after that to boot. She will have to appear at all five functions, looking her absolute best at each. She is, after all, a lady now. Society expects her to.

The world of the privileged may glitter. It may be full of luncheons, evening shows, and ballroom dances that go on till the stars have gone[26], populated with the sons and daughters of silk barons and railroad kings. But in this world of luxury and convenience there’s a steep price to pay for any young lady with the faintest hopes of succeeding in it. It comes in the form of her time. Her money, generously supplied by her father. Her mettle and mental fortitude. Not even twelve hours after her own coming-out Mae will be expected to plunge headfirst into society’s gauntlet of social events, looking always sharp, lively, and well-put together, finding the time to squeeze in appointments with her modiste and her hairdresser, and perhaps to eat something too. To put it in the words of a well-seasoned society belle:

Generally I rise about 10 o’clock and breakfast while my maid brushes my hair. Then at 1 I am off to a luncheon, and only leave to attend three or four receptions. Home again at half-past five to dress for a dinner party, and then to the opera, and frequently a ball after the opera. At 2 or 3 in the morning I am ready to go to bed, and this is the life I have led for the past two seasons.[27]

The life of a society woman is a blur of parties and picnics, stumbling from one day to the next until, at some point, night and day appear the same. Mae sleeps when, and if, she can.[28]

It will be noted amongst the Four Hundred how Miss Mae comports herself in public. As a potential match for the eligible bachelors amongst the elite, everything about Mae will be observed by the calculating eyes of society’s established set. Her father is the president of the First National Bank—she ought to know how a rich young woman ought to behave. Does she dress appropriately for her age and station? Does she use slang when speaking to others? Does she wait for her guests to be seated before seating herself, as a good woman and hostess should? Has she ever been caught smoking a cigarette, having a drink, or talking to a young man she does not know, in a place she shouldn’t have been?…Mae knows full well that many a young bud’s hopes have been dashed for infringements such as these. The world of the elite can be just as cruel as it is charming—perhaps none more so than when it comes to how successful Mae is in scoring a husband. She knows the criteria her potential spouse must meet for her to be considered a success amongst her peers. He must be respectable, well-educated, and of impeccable family pedigree—the kind of man who counts former presidents and European aristocrats amongst his relatives. And above all, he must be unfathomably rich.

Perhaps Mae would sympathize with a humorous fictional story published in the papers a few years after her coming-out. It focuses on the fictional Marjorie Dean, a society woman in her mid- to late-twenties who is headstrong and unwilling to settle for a man without money. Her capricious ways have almost driven her mother to madness—forcing her to remind her daughter that her debutante season, and all the hope and promise that came with it, is now a distant memory. The only fate worse than marrying a poor man’s son is not marrying at all[29]—and so it comes as a surprise to everyone when Marjorie falls in love with a pleasant, soft-spoken clerk for a local bank.

True, the story ends with love conquering money as the barometer of a successful relationship—but the horror Marjorie’s mother shows at the news (not to mention the mortification of all the rich young bachelors who had been chasing Marjorie’s hand) stand in stark contrast to her decision. Love and marriage amongst the elite are not arranged according to one’s feelings. Marjorie and her beau’s relationship is a shameful scandal amongst all the society people who know her—a dire warning to any rich young woman in the real world who would dare jeopardize her family pedigree and social standing for the sake of a genuine romance.

So much as we can tell, Mae refrains from following in Marjorie Dean’s footsteps. She marries Edward van Ingen, a man who graduated from Yale and hails from a family of “high social standing”[30], on January 25, 1897.

~

ONE-HUNDRED and thirty-two years on, the daughters of hedge-fund owners and real estate giants make their formal entrances to society at the International Debutante Ball. Naturally, it’s wildly exclusive–only those who receive a personal recommendation from a former debutante are allowed attend[31]. As tradition goes their gowns are white and “oh, so simple”, made by exclusive fashion houses in New York and Paris. Almost all of them are college-educated. Some are models, others scientists, still others doctors and lawyers. The American debutante of today knows which utensil to use at what meal during a banquet, and how to negotiate a salary in accordance to what she is worth[32]. There is no talk of courtship and old-money heirs. Instead, her coming-out is mere practice in networking amongst peer parent’s peers.

Maybe Mae would be jealous of today’s debutante: the burning white lights of society no longer focused so intensely on her appearance and her character, her quest no longer expected to end in marriage by the close of her first or second season. However, just as it was in Mae’s day, the mere act of coming out still carries a hefty amount of weight amongst the world’s elite. Very few young women can claim to have been the star of an elaborate performance put on just for her. Never mind having grown up wealthy enough to entertain a world where everything money can buy—from material possessions to business connections—lies open for the taking upon her eighteenth birthday.

Footnotes

[1] “Mae Bell’s Debut: An Elaborate Society Event on Broadway”, The News, Saturday, Dec. 19, 1891; accessed November 9, 2023, from Newspapers.com

[2]“Teas Innumerable Have Been and Are To Be”, The Sun, Sunday, Dec. 4, 1880; accessed November 9, 2023, from Newspapers.com

[3]The mainstream press overwhelmingly covered coming-out parties of wealthy white families. The tradition of wealthy African American families hosting debutante cotillions for their daughters can be traced back as far as 1895, in New Orleans, Louisiana. “Buds of Washington: Margaret Manton Tells of the Capital’s Pretty Girls”, The News, Thursday, Jan. 8, 1891; accessed November 9, 2023, from Newspapers.com

[4] Miss Julia Grant, for instance, was the granddaughter of former president Ulysses S. Grant. She made her debut to New York society in December 1893—after having made her bows in the royal courts of Vienna, Austria.

[5] Ibid.

[6] In the case of Miss Hopkins, daughter of a Washington senator, she attended Ferry Hall College in Illinois and graduated as valedictorian of her class.

[7] “Buds of Washington”, The News, Thursday, Jan. 8, 1891.

[8] As Margaret Manton put it: “She can fence, and—tell it not in Gath—there are a few of her who can send a football spinning into the air in a way that would make a Yale halfback ashamed of himself.” Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] “Young Official Set: New Factor in Society and Politics at Washington”, The News, Saturday, Apr. 9, 1902; accessed November 9, 2023, from Newspapers.com

[11] Ibid.

[12] “Debutante Now Holds Social Stage’s Centre”, The Morning Call, Saturday, Nov. 13, 1915; accessed November 9, 2023, from Newspapers.com

[13] C., N. “Chapter 1”, “Chapter 3” in Practical Etiquette. A. Flanagan: Chicago, IL, 1899. Accessed Dec. 5, 2023, from the Library of Congress (www.loc.gov)

[14]Green, W.C. “Afternoon Teas”, “Balls”, “Balls for Debutante”, “Dances” in The Book of Good Manners: A Guide to Polite Usage For All Social Functions. Social Mentor Publications: New York, NY, 1922. Accessed Dec. 5, 2023, from the Library of Congress (www.loc.gov)

[15] By the 1930s, hotels such as Pierre’s, Sherry’s, and the Waldorf Astoria made almost half a million dollars alone hosting coming-out parties.

[16]“Debutante Now Holds Social Stage’s Centre”, The Morning Call, 1915.

[17] “In Training for the Campaign”, The Morning Call, Saturday Feb. 20, 1886; accessed November 9, 2023, from Newspapers.com

[18] Ibid.

[19] “The Hebrew Charity Ball: Many Present in Spite of Inclement Weather—Wealth and Fashion Make Merry All For Sweet Charity’s Sake”, The News, Thursday, Jan. 21, 1897; accessed

[20] “Mae Bell’s Debut”, The News, 1891

[21]“Debutante Now Holds Social Stage’s Centre”, The Morning Call, 1915.

[22] “In Training for the Campaign”, The Morning Call, 1886.

[23]“An American Girl at Court, As Told By Herself,” excerpt from the Ladies’ Home Journal, Vol. 9, 1891. Accessed November 9, 2023 from mrs.daffodialdigresses.wordpress.com

[24]“A Fair Debutante at a Late Ball,” New York Tribune, Sunday Jan. 18, 1880; accessed November 9, 2023, from Newspapers.com

[25] [25]Green, W.C. The Book of Good Manners: A Guide to Polite Usage For All Social Functions. 1922.

[26] Lyric from the chorus of “After the Ball”, a popular song of the time.

[27] “In Training for the Campaign”, The Morning Call, 1886.

[28] Ibid.

[29] “The Day Will Come”, The News, Tuesday, Dec. 1, 1896; accessed November 9, 2023, from Newspapers.com

[30] “Miss Mae Bell, the only daughter of Mr. E. T. Bell, President of the First National Bank,” The News, Monday, Jan. 4, 1897; accessed December 10, 2023, from Newspapers.com

[31] “It’s Easy to Dismiss Debutante Balls, But Their History Can Help Us Understand Women’s Lives”, by Kristen Richardson, Time, Nov. 25, 2019. Accessed on Dec. 10, 2023, from Time.com.

[32] “What it Means to be a Debutante Today”, by Vivian Manning-Schaffel, published Dec. 22, 2020. Accessed Dec. 13, 2023, from Shonadland.com

Bibliography

Books:

C., N. “Chapter 1”, “Chapter 3” in Practical Etiquette. A. Flanagan: Chicago, IL, 1899. Accessed Dec. 5, 2023, from the Library of Congress (www.loc.gov)

Green, W.C. “Afternoon Teas”, “Balls”, “Balls for Debutante”, “Dances” in The Book of Good Manners: A Guide to Polite Usage For All Social Functions. Social Mentor Publications: New York, NY, 1922. Accessed Dec. 5, 2023, from the Library of Congress (www.loc.gov)

Articles:

“A Fair Debutante at a Late Ball,” New York Tribune, Sunday Jan. 18, 1880; accessed November 9, 2023, from Newspapers.com

“An American Girl at Court, As Told By Herself,” excerpt from the Ladies’ Home Journal, Vol. 9, 1891. Accessed November 9, 2023 from mrs.daffodialdigresses.wordpress.com

“A Pretty Debutante: Miss Helen Griggs Makes Her Debut Into Society At An Afternoon Tea Yesterday”, The News, Thursday, Dec. 10, 1896; accessed November 9, 2023, from Newspapers.com

“A Word to the Debutante”, The Morning Call, Tuesday, Oct. 24, 1911; accessed November 9, 2023, from Newspapers.com

“Among the new senatorial families”, The Morning Call, Saturday March 28, 1903; accessed November 9, 2023, from Newspapers.com

“Born in the White House”, The News, Saturday, Dec. 16, 1893; accessed November 9, 2023, from Newspapers.com

“Buds of Washington: Margaret Manton Tells of the Capital’s Pretty Girls”, The News, Thursday, Jan. 8, 1891; accessed November 9, 2023, from Newspapers.com

“Costlier Parties Given to Usher in New Debutantes”, The News, Friday, Dec. 27, 1935; accessed November 9, 2023, from Newspapers.com

“Debutante Now Holds Social Stage’s Centre: Question of Clothes Forms an Ever Perplexing Problem for Mothers of Girls in Moderate Circumstances—Simplicity in Dancing Frocks Add to the Charm of Her Coming Out”, The Morning Call, Saturday, Nov. 13, 1915; accessed November 9, 2023, from Newspapers.com

“Debutante Season at Peak in New York: Fashionable Hotels See Parties Every Evening During Busy Week”, The Morning Call, Saturday Dec. 27, 1930; accessed November 9, 2023, from Newspapers.com

“It’s Easy to Dismiss Debutante Balls, But Their History Can Help Us Understand Women’s Lives”, by Kristen Richardson, Time, Nov. 25, 2019. Accessed on Dec. 10, 2023, from Time.com.

“In Training for the Campaign”, The Morning Call, Saturday Feb. 20, 1886; accessed November 9, 2023, from Newspapers.com

“Mae Bell’s Debut: An Elaborate Society Event on Broadway”, The News, Saturday, Dec. 19, 1891; accessed November 9, 2023, from Newspapers.com

“Miss Mae Bell, the only daughter of Mr. E. T. Bell, President of the First National Bank,” The News, Monday, Jan. 4, 1897; accessed December 10, 2023, from Newspapers.com

“Mrs. A. M. Palmer’s Reception: A Throng of Well-Known People Help Usher a Bud Into Society”, The Sun, Saturday, Feb. 8, 1890; accessed November 9, 2023, from Newspapers.com

“Now to Christmas the Debutante’s Special Reign – ‘Middle-aged’ Materials – How the Debutante’s Garb Differs from the Young Matron’s – The Evening Wrap Girlish in Style – Bewitching Bonnets on Youthful Faces”, The News, Monday, Nov. 29, 1909; accessed November 9, 2023, from Newspapers.com

“Social Life in Washington: Daughters of Justice Harlan and Chief Justice Fuller Introduced to Society”, The Sun, Saturday, Jan. 4, 1890; accessed November 9, 2023, from Newspapers.com

“Teas Innumerable Have Been and Are To Be”, The Sun, Sunday, Dec. 4, 1880; accessed November 9, 2023, from Newspapers.com

“The Day Will Come”, The News, Tuesday, Dec. 1, 1896; accessed November 9, 2023, from Newspapers.com

“The Debutante: Charming Frocks She May Wear to Dinner and Dances”, The Morning Call, Saturday Jan. 15, 1910; accessed November 9, 2023, from Newspapers.com

“The Hebrew Charity Ball: Many Present in Spite of Inclement Weather—Wealth and Fashion Make Merry All For Sweet Charity’s Sake”, The News, Thursday, Jan. 21, 1897; accessed

“What it Means to be a Debutante Today”, by Vivian Manning-Schaffel, published Dec. 22, 2020. Accessed Dec. 13, 2023, from Shondaland.com

“Young Official Set: New Factor in Society and Politics at Washington”, The News, Saturday, Apr. 9, 1902; accessed November 9, 2023, from Newspapers.com